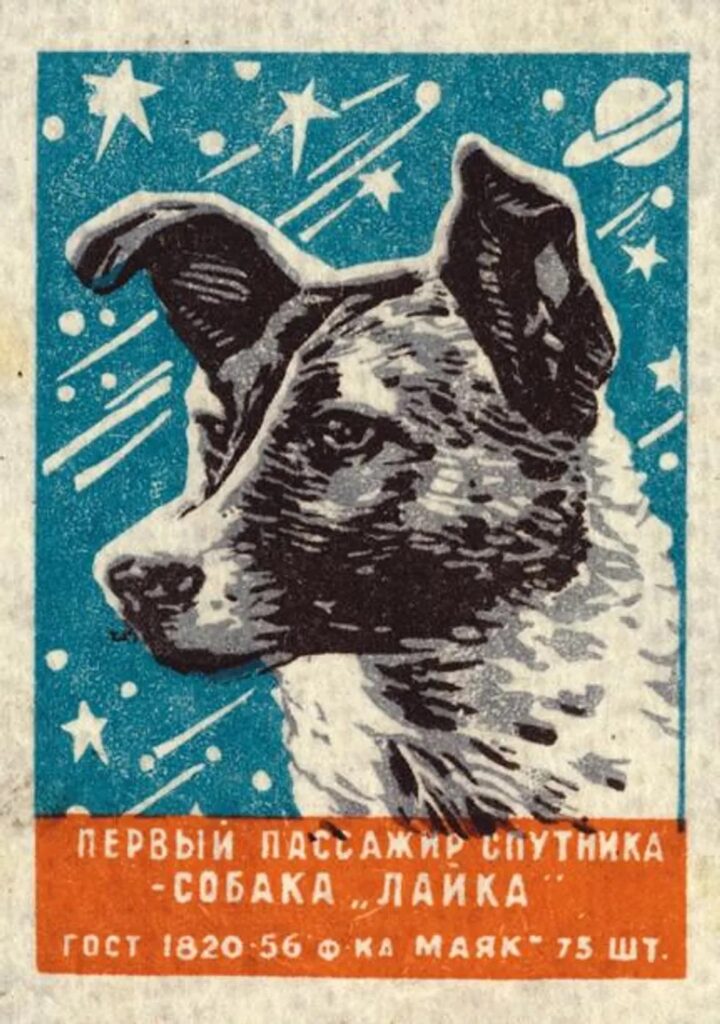

If you’ve ever heard the story, or studied it, or if perhaps you yourself even remember it from broadsheets, newsreels, and primitive network newscasts, there’s one photograph in particular that likely defines it. She—a small, perhaps Terrier-ish female—is standing in her vessel. She’s alert. And seemingly cheerful. The energy, even in black and white, appears akin to that of the very happiest of domestic dogs. She might be ready to bound across the lawn. She might’ve just heard beloved footsteps.

The truth of the moment was slightly different. The little Husky/Terrier mix had been discovered and captured by Soviet scientists on the streets of Moscow. Flinty, unassailable Russian pragmatism held that any stray that could withstand the rigors of street life and the brutal winters of the capital would have the best possible prospects for success in her unprecedented State mission to come. During an evaluation process alongside other Moscow strays, she was for a brief time designated Kudryavka (“Little Curly”) by her masters. Later in her training, she became identified with, and by, her loud barking.

Laika (“Little Barker”) was hurled into space, into international fame, and ultimately, into history aboard Sputnik 2, riding atop a Soviet missile launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome on the morning of November 3, 1957. The trip, in history’s second-ever manmade satellite, made her the very first Earth inhabitant to ride into orbit and the first to glimpse the planet from high on this newest, most sprawling frontier. Soviet Premier Nikita Krushchev, who had demanded a public relations coup to accompany that November’s 40th anniversary of Lenin’s triumph at Petrograd, now most certainly had it. A new Hero of the Soviet Union! An intrepid scout to the heavens, bravely and dutifully preparing the way for the men (and women!) of the USSR to follow. Laika was an international sensation—a figure of fascination and awe. She was beloved and celebrated outright in the Eastern Bloc. And in the West, the images of the beautiful little dog took some edge off the ominous implications of Soviet spaceflight. The technological achievement—and possible menace—was softened by the face of an adorable little explorer. NASA would follow with chimpanzees, but not until nearly four years later, in 1961. And the effect would never be the same. Man’s closest animal relative somehow failed to claim the heart nearly so well as his best friend had.

Is it a surprise that this should be so? Even set against the backdrop of the cruelty and terror of the Soviet regime, there’s a kind of enduring perfection, a triumph in the flight. Somehow, it seems inevitable that a beautiful, spirited little mongrel came to be our very first emissary to the stars. If mankind was embarking on a grand new adventure, how could its companion be other than a dog?

***

19th century painting of Pointer and Setter on the hunt.

Getty Images/ C.F. Deiker

Oberkassel, Germany lies on the western bank of the Rhine, tucked within the greater municipal area of the city of Bonn, roughly 1,300 miles west of the Kremlin. On the morning of Sputnik 2‘s flight, the city was serving as the capital of a free West German state very much imperiled by the missiles of the Soviet Union. Little Oberkassel held its own secret that day. A prehistoric gravesite collection of human and “animal” bones unearthed during basalt mining in the district in 1914 and given some further examination five years later, was…gathering dust. As it would for an additional two decades after Laika’s voyage. By the time the trove was revisited in the late 1970s, the “animal” or perhaps “wolf” bones, buried quite deliberately alongside those of a man and a woman some 14,000 years earlier, could at last be refigured in the light of new advances in scholarship and technology. More than sixty years after they had been initially thought to represent a crime scene, or later, a trace of the far reaches of the Roman Empire, the bones of Bonn-Oberkassel were ready to tell a new Paleolithic tale about humans and their dogs.

The “wolf” of the German site has, via DNA testing, proven to be a wolf of a genetically different sort: Canis lupus familiaris—a dog, one descended from an ancient and now-extinct wolf population. That population, itself quite distinct from the forebearers of contemporary wolves, became the basis of five ancestral lineages of dog. In turn, these lineages have created the basis for an ancient and modern dog population structure that is generally classified into Arctic/Americas, East Asian, and West Eurasian. These populations have roamed and settled across the continents, while periodically admixing. Usually, but not always, change and development in the canine genetic record tracks with contemporaneous population movements of humans. East Asian dog populations have been relatively isolated both physically and genetically; European, American, and Arctic populations have mixed far more extensively. Modern African dogs are descended from the West European population. Dogs appear to have arrived in the Americas via Siberia, but unaccompanied by any major human population movement. The exact nature of this migration remains something of a blind spot in the field of study.

It’s a longstanding and of course highly sturdy theory that the basis of active partnership between humans and a dog that was distinct from the wolf would have been in hunting. That bargain, with survival and reproductive advantages for both species, likely originated in scavenging and begging on the part of dogs—something to consider when trying in vain to discipline a Labrador near the dinner table. From the first, humans gave dogs a place to be, and a place to beg. Hunting, and the ever-more-refined participation of dogs in the practice, progressed as the glaciers of the Late Pleistocene receded and growing forests became more promising habitats for prey. Archeological sites in Saudi Arabia contain 8,000 year-old carved renderings of leashed dogs aiding their humans in the hunt. A dazzling (and to this day still not fully understood) sense of smell and a swiftness that no human could match made the partnership far more mutual—more equal, even—than we humans might care to admit. Man’s capacities for planning and coordination were now extended by gifts for vigilant hearing, tracking, and for swift and spirited execution. Still well before the dawn of recorded history, burial evidence from across cultures and across the planet, from Japan to Africa, reveals that the dog was venerated both in life—and afterwards—as a living weapon.

***

Chairman Krushchev, in those matters of “planning” and “coordination” having to do with political glory, was especially demanding and ruthless in 1957. That October’s triumph of Sputnik 1 had whetted the Premier’s appetite for an immediate and spectacular follow-up keyed to the traditional November 7th anniversary of the 1917 Bolshevik victory in Petrograd. The political imperative left essentially no time for the proper preparation of a Sputnik 2 spacecraft. By the time the decision to proceed was officially taken on the twelfth day of October, engineers had four weeks to design and build the spacecraft in which Laika was to make history. Even by the secretive and harsh standards of the regime, the undertaking was preposterous: the technology to build a spacecraft and a flight plan that could return a living subject to Earth remained years out of reach for either the Soviet Union or the United States in 1957. But the USSR had something to prove, and Laika, newly off the Moscow streets, would give her life for its prestige.

When she departed from Baikonur for the heavens, the first cosmonaut was chained and harnessed in a padded cabin that allowed just enough room for her to sit or to stand. She was fitted with electrodes to monitor temperature, heart rate, and breathing. Food and water aboard the primitive spacecraft were carried in gelatinized form. A small porthole represented both a surprising advance in design and construction and a surprising amenity. The launch itself imposed a load of more than five times that of Earth’s gravity. Combined with the roar of the rocket, it sent her heart racing to three times its resting rate—essentially, a state of terror. The scientists hoped that she might survive aboard her tiny craft for as many as ten days.

***

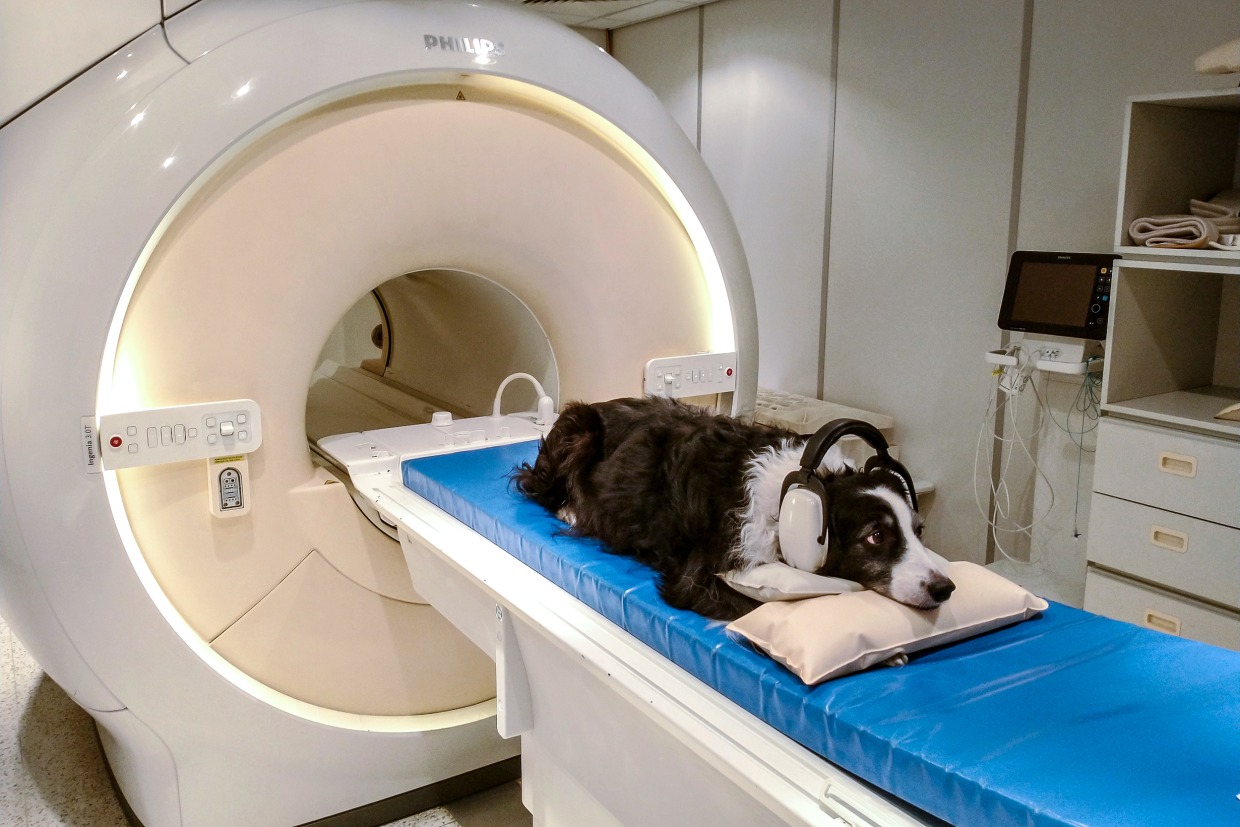

A stamp commemorating the heroic and iconic dog.

The burial ground at Bonn-Oberkassel, which had already sat undisturbed for six millennia when the 8,000 year-old Arabian hunting images were created, ultimately offered a story deeper and richer than that of a practical partnership. The dog, placed carefully with the man and woman, was a late juvenile at the time of its death at the age of around twenty-eight weeks. Lesions in its oral cavity indicated unmistakably that it had been ill for at least the last ten weeks of its life, and that the illness reached grave severity in the dog’s final four weeks. By 2018, the French veterinarian/archeologist Luc Janssens, writing for the Journal of Archeological Science, had concluded definitively that the dog at Bonn-Oberkassel would have required “intensive human assistance” for any prospect of survival, and that well before this period of its short life, it could not have “held any utilitarian use to humans.” More than 12,000 years before the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, two human beings—she between twenty and twenty-five at death, he between thirty-five and forty-five, and likely together as mates—had demonstrated a deep and sustained care bond with a dog that could offer them no help whatsoever with their own fortunes and fate. And whether they eventually outlived their sick dog by days or by years, the people to whom their burial had fallen made sure that the pair was laid to rest together—and together with their dog.

The depth of commitment and of ritual makes it well-nigh impossible that Bonn-Oberkassel was some kind of fluke or innovation. But how well-established might the German practices have been? Archeologist Keith Dobney of the University of Liverpool has reached another thousand years back beyond it. While the German site remains the oldest canine-human burial site yet discovered, Dobney has posited that domestication was by then long-established. “On the basis of the current data,” he told National Geographic in 2018, “it’s clear that we had domestic dogs by at least 15,000 years ago. How much earlier domestic dogs existed is up for debate, with some people saying they might go back to 30,000 years ago.”

Partnership and affinity across any of these vast spans is as staggering as its ultimate origins are—at least as yet—unclear. What is clear and definitive, however, is that the bond and shared destiny of canine and human precedes our species’ connection with any other animal of any other character or purpose. There is no domesticated animal to even approach the dog for duration of service. And certainly no other animal with whom we have shared so much affection for so long.

This tie is indicated across the genetic record by what is known as “convergent evolution,” in which two unrelated species independently select for and evolve solutions to environmental challenges experienced together. As canines and humans have ventured to different climates, altitudes, and ecosystems, the evolutionary lines have responded in parallel. The long, slow sorting of the ages, in which dog and human populations refine collaborative survival in often hostile settings is its own kind of organizational miracle, and something that we tend to intuitively take for granted. The Inuit hunter with his Qimmiq Canadian Husky makes sense because both their lines outlasted those of their less well-adapted rivals. The Boerboel, the South African farmdog, and its cousin, the Rhodesian Ridgeback, serve human agriculture in ways that overlap widely, yet with distinct and highly specialized emphases on protection vs. hunting. Thousands of generations of selection are behind the everyday actions of these breeds.

And convergence of course doesn’t end in the field. Certainly, it has behooved dogs to develop highly specialized skills for reading human facial and body languages, and for grasping human social communications. Most anyone who has travelled through the grief of death or divorce alongside the close companionship of a dog knows well the potent—the palpable—sense of understanding and connection. That feeling that one’s dog is far more attuned to the inner life than any of one’s supposedly more sophisticated human allies. By 2015, Japanese researchers had begun to give this phenomenon a hard physiological basis. Oxytocin levels, in both dogs and their human companions, rise in response to mutual eye contact—just as they do in human maternal bonding. The chimpanzee, with whom we share so many genes, doesn’t begin to match the levels of human connection and understanding exhibited by the dog. Nature and nurture have done their parts.

***

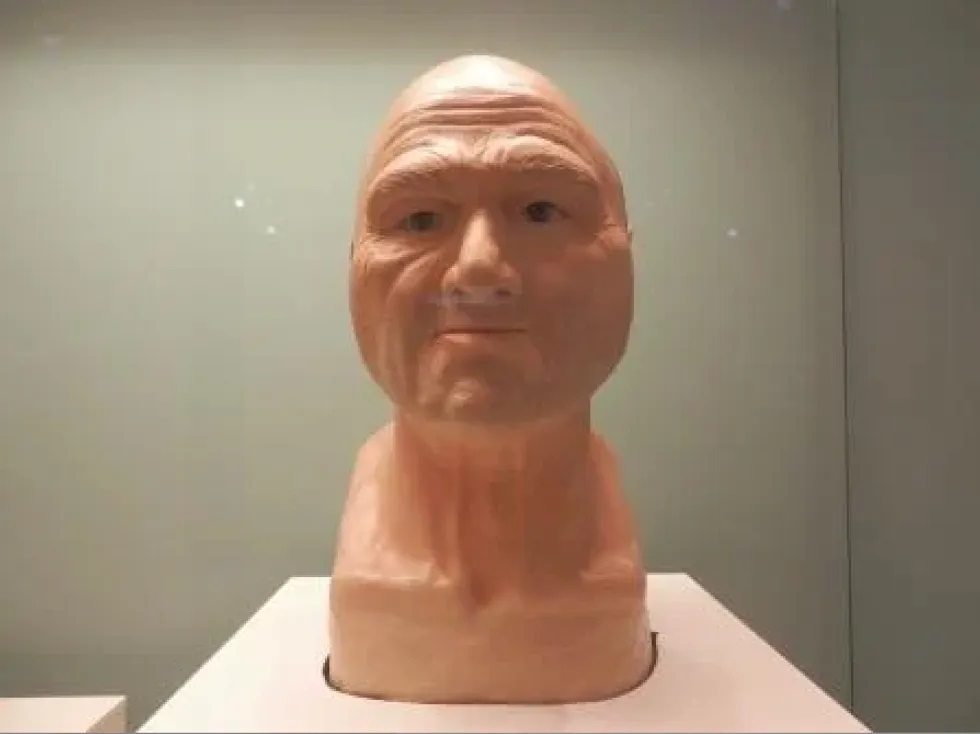

Facial reconstruction of the man from the burial ground at Bonn-Oberkassel.

Reconstruction of the dog from the burial ground at Bonn-Oberkassel.

Facial reconstruction of the woman from the burial ground at Bonn-Oberkassel.

The official Soviet news agency TASS claimed that Laika lived for a week, streaking effortlessly over and around the globe. But the truth, revealed via a 2002 unsealing of confidential Soviet-era archives, as well as new interviews with surviving flight scientists, was that measures meant to protect the cabin from the sun’s harsh rays had failed almost immediately. Some sort of habitable environment appears to have been maintained for perhaps three orbits, but shortly afterwards the temperature in the tiny cabin soared to 109 degrees. Telemetry indicated that she was moving—and perhaps exploiting her sudden weightlessness—just before signs of life from Sputnik 2 quickly ebbed. No breathing, no heart rate, no blood pressure. Even with these vitals flat, the heart rate sensor registered an eerie, faint heartbeat for some additional hours. By the morning of November 6th, 1957, she was gone. Spacecraft batteries lasted an additional four days. Laika was returned to her home planet only by the disintegration of Sputnik 2 somewhere in the sky over the east coast of North America early in the following spring.

***

By 2002, the same year in which Sputnik 2‘s planners were lifting the old propaganda veil on the facts of Laika’s suffering and death, Dr. Paul Tacon of the Australian Museum and his archeologist partner Dr. Colin Pardoe, were ready to present the fruits of their years of research into the earliest domestication of wild dogs. “We were asking the questions, ‘What is a human?’ and ‘what is a dog?'” Tacon would later say. “The answer was not straightforward and we found that the two were intertwined.” The farther and wider the two men looked into the archeological and genetic records, the more the traditional top-down story of wolves domesticated and elevated by humans had begun to fray.

Tacon and Pardoe, drawing on fossils and genetics, postulate that the relationship began 100,000 years ago. It’s a timeframe that makes Bonn-Oberkassel seem nearly as recent as 1957. Their work supposes the benefits to nomadic hunter-gatherer camps of humans. Along with the improvement to sanitation realized by scavenging for food scraps, these earliest companions would have served as alarms for the camps, warning of rivals and predators. As the mutual dependency and trust deepened, the familiar role as hunter was to emerge. But the dramatic turn of the Tacon-Pardoe story is the recognition that the territorial and social traits that we casually credit to humans—the complex alliances and interdependency, the basic tribal scope of human concern revealed in caring for the group’s young and not merely one’s own, and even the coordination and planning of the hunt itself—actually originated with the wolves-cum-dogs of earliest Homo Sapiens. Indeed, the traits and habits that broke us successfully away from our doomed Neanderthal cousins are the very same ones brought to us by dogs. Dogs watched and adapted to humans. But humans, by emulating dogs and by caring for them, actually became humane. Like the bumper sticker says: “Who Rescued Who?”

***

Standing aside as they did from the superpower competition of the Sputnik moment, the British seem to have possessed the most immediate moral clarity about the loss of a living creature to the enterprise of spaceflight. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals began receiving calls of protest while Radio Moscow’s announcement of the flight was still in progress. And even as the world was being led to believe that Laika was still alive in orbit, the BBC could report that the National Canine Defence League was “calling on all dog lovers” to observe a minute’s silence during every day she remained in space. Eventually, the RSPCA would call successfully for protests in front of the Soviet embassy near Kensington Palace. The instantaneous uproar in the UK would bleed outward into global reflections on the flight, complicating the intended public relations message of sensational Soviet technical prowess. Rather than offering an outright propaganda victory, the use of a vibrant little dog had stirred the West’s sense of a haunted brutality behind the Iron Curtain. An anonymously written poem condemning both the mission and the Soviet state was circulated through Moscow at a time when association with such material would’ve meant a trip to the gulag. Out beyond the ring of submissive Soviet client states, Chairman Krushchev’s prestige chalice had been, at the least, sharply tainted. Dogs, it turned out, were still teaching us to be human.

But in the end, those most affected by Laika’s whirlwind trip from the Moscow streets to Baikonur in Kazakhstan and then to the void, were the doctors and engineers who had so brilliantly served the Soviet Union. With the 2002 Russian declassifications and releases of materials surrounding the episode, their voices and perspectives began finally to emerge. A number of the staff of the Air Force Institute for Aviation and Medicine came forward to reconsider the dog’s sacrifice and even to condemn outright the ethics of her use. She was pretty, they remembered, and her photogenic quality had likely played a role in her ultimate selection. Her closest rival candidate had recently had a litter of puppies and was therefore spared. Even in the short weeks before her flight, they had enjoyed her. She was given unauthorized rations immediately before being sealed aboard Sputnik 2. In her last days before the trip to Baikonur, Dr. Vladimir Yazdovsky, the program’s director and a member of the very highest echelon of Soviet space decisionmakers, snuck her away from the facility for an evening with his children. For just a moment, the competition with the Americans, the pressures of Party loyalty, the ego, the drive, even the demands of the Chairman himself, faded away. “I wanted to do something nice for her,” he remembered. “She had so little time left to live.”