Argos

Rufus Gifford and Dr. Stephen DeVincent met in February of 2009 in Washington, D.C. Rufus had been working on the Obama campaign and now was shifting over to become the Finance Director for the Democratic National Committee. Stephen, a veterinarian, was in town on a fellowship with the State Department in the Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs, focusing on polar bear policy. As Rufus remembers, “From 2009 on, there was only one person I noticed.” The following year, they moved in together, and in January of 2012, they got their first dog—a beautiful Golden Retriever who would become the center of their lives.

They named him after Odysseus’ dog, Argos—the first great dog of literature. In the epic tale, Odysseus has been gone from home some twenty years—has fought in Troy, been blown by Poseidon to the edge of the seas, resisted the call of the Sirens—and when he finally returns, no one can even recognize him except for his faithful dog. Ancient and flea-bitten and neglected, Argos sees his old, forgotten friend, and wags his tail.

Svend in repose.

Photo by Rufus Gifford

The Grand Bargain

Rufus mentions the origin of their dog’s name because he and Stephen and Love, Dog’s founder, Mark Drucker, and I are all talking about the history of canines and humans, and Homer composed The Odyssey some 2,700 years ago. It’s amazing how even then, all the qualities we hold so dear in dogs today were already evident in that first noble dog—faithfulness, friendship, and perhaps most of all, heart. Of course, the story of dogs and humans began long before that, though as we chat, none of us can remember exactly when—15,000 years ago? 20,000? 35,000? But the number is less important than the nature of the connection itself, and how that indelible bond must first have been formed: “All domesticated animals were domesticated for a reason,” Stephen says, “dogs and horses especially. There’s a balance or exchange that they made with us. And wolves were smart enough to realize there was benefit there for them in this symbiotic relationship between man and animal: that they would be provided for, get food and shelter, get to sleep on the bed. It was the grand bargain—a deal, so to speak.”

What we humans were getting in return is, in a certain sense, unclear—or, at least, not completely obvious. Even Stephen does not name it right away. Sure, originally, all those thousands of years ago, what those first tamed wolves were giving our ancestors as they sat around the campfire was, in part, simple—sensitive ears to notice a predator’s approach in the night, or an enemy’s. And over the ensuing millennia, canines have offered their services in myriad other ways, too—they have been guard dogs and attack dogs, they’ve hunted rats and foxes and lions, they’ve been shepherds and guides.

They gave us something else in that ancient exchange, too, though—something more abstract, yet also more substantial. Love, yes; companionship, yes. But more than all that—or perhaps through all that—dogs opened us up, somehow, exposed something soft within us. Stephen quotes Anatole France as saying, “Until one has loved an animal, a part of one’s soul remains unawakened.” And that’s it, I think, or part of it: dogs gave us the gift of awakening. They expanded our lives, our sense of who we were, and who we could be. It was true 35,000 years ago and it is true today: dogs allow us to be our best selves. Quite simply, they make us more human.

President Obama straightens Rufus’ bowtie at the Nordic State dinner held at the White House in May 2016, as Stephen looks on.

Photographer: Anonymous

The Diplomatic Dog

“The relationship between Washington, DC and dogs is legendary,” says Rufus, who, like Odysseus, is no stranger to the world of politics. An integral part of the victorious Obama and Biden campaigns, and the former US Ambassador to Denmark, Gifford is now President Biden’s Nominee to be Chief of Protocol for the United States, a role he describes as being the primary liaison between the Biden administration and foreign governments. Whenever the President or other senior White House officials travel overseas, the Chief of Protocol travels with them, and is an active participant in all of the President’s global engagement.

When I ask Rufus about the role of dogs in politics, he laughs and quotes Harry Truman: “If you want a friend in Washington, get a dog.” But dogs in D.C. don’t just function as one’s only possible loyal companions—they also serve to make a president, for instance, more accessible. It’s strange to think that another species would be the thing that would somehow make us more human, but so it is. “Dogs humanize powerful people in a way that nothing else can,” he explains.

But Rufus is less skeptical about the political world—and the strangely integral role dogs play in it—than one might expect: “You could look at this cynically—like, this is why politicians get dogs, because it humanizes them—but I think it’s real, too. I remember not liking George W. Bush one little, tiny bit. But hearing him talk about Barney, which is this little terrier Toto kind of dog, there was this tremendous amount of love in his voice, which was very, very different from the way he talked about other things.”

Chiming in, Stephen mentions Richard Nixon’s famous speech about his dog, Checkers—and we all talk for a moment about how it wasn’t exactly surprising that Trump was the first president in more than 100 years to not have a dog in the White House. Then Rufus goes on to describe one of his favorite moments of the early Biden administration: a press gathering in the Oval Office. “It was like a live stream that you saw—you know, they try to orchestrate these perfect little photo ops—but you could hear Champ and Major, his two dogs, barking somewhere on the grounds in the background—they were probably rolling around the beautiful south lawn. And there was something so incredibly normal about that, so real, especially after the Trump administration, which felt so fake in every way and so inhuman. Somehow, the fact that Champ and Major were barking in the background of some very official, serious Oval Office press moment, it felt so wonderfully disarming.”

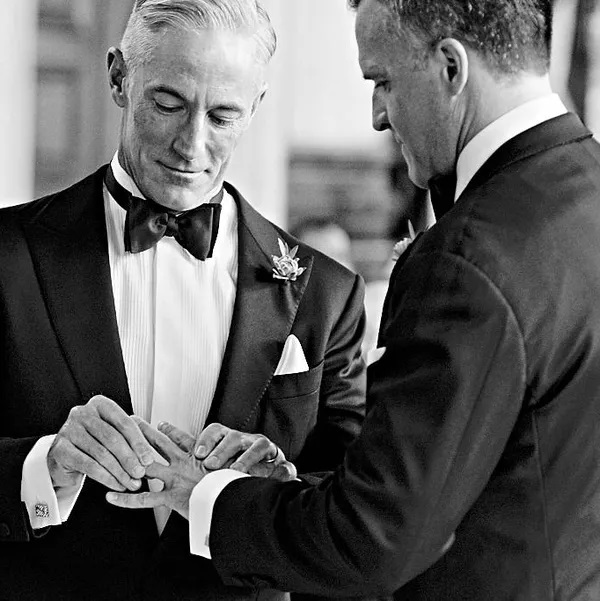

Rufus and Stephen tying the knot on October 10, 2015, in Denmark.

Photo by Peter Brinch

Rufus, Argos, and Svend hugging it out.

Photo by Stephen DeVincent

Leading with Your Heart

There’s something wonderfully disarming about Rufus, too—as a human being, and also as a diplomat. When he enters a situation, or meets someone new, he puts his heart on the table—which is, as he points out, exactly what dogs do. “When a dog approaches you, they lead with their heart. Those are the dogs that I think we all fall in love with, the ones who go in very open-hearted—that’s what allows you to sort of give in and bond. And in my work as a diplomat, I always try to come into any conversation and show everybody exactly who I am in a very honest and transparent way.”

It’s ironic, perhaps, that in a realm so often defined by deception and cunning, by pretending—that Rufus’ method is simply to be himself—but it seems to work. It softens people, disarms them, lets them know it’s OK for them, too, to open up. No longer is it two politicians, with all their hidden motives and desires, but just two human beings, being themselves. “In an increasingly virtual and disconnected world, to try to connect human to human, in the same way that sort of dogs and humans connect—it really does matter.”

There is of course great risk in going into any relationship with such openness and heart. It requires a kind of trust that’s hard to find these days in anyone—except, perhaps, once again, in dogs. “Dogs give you the benefit of the doubt,” Rufus continues. “So, in an age when trust is sort of at an all-time low, and we don’t trust anybody—we don’t trust political leaders, we don’t trust business leaders, we don’t trust the media—dogs do trust. They go into a situation with a new person trusting that you are going to be nice to them, that you’re going to, you know, throw the ball for them. And there’s something so beautifully kind of optimistic about that.”

Rufus and Stephen both recognize that not all dogs are like this—that just as with humans, dogs who have been abandoned or abused can lose this ability to trust—but Rufus believes that this open, loving nature is their true state, and that it is our own true nature, too. “In my life, in my work—and Stephen knows this—I’m obsessed with this idea of human trust. We insist, because we’ve been burned over and over again, on viewing situations with a certain degree of skepticism. But wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could trust a new person in the same way a non-wounded dog trusts a new person? Somehow, we’ve got to build that trust back. And if you think about a model for that—and this is connected to putting your heart on the table—it’s disarming folks just like dogs disarm you when they look at you and wag their tail.”

At home in Nantucket, Rufus spent his birthday with those he loves most.

Chest up: Rufus doing his best to look professional while preparing to brief @joebiden supporters on Zoom. Chest down: wearing gym shorts and sandals and being harassed by Argos and Svend.

Photo by Stephen DeVincent

Home is Where the Dog Is

“As soon as we got Argos—I was working on the Obama campaign at the time—I fell in love with him in a way that I didn’t know that I could,” Rufus confesses. “He is the least easygoing dog I’ve ever met. He hates the car, he hates swimming—all the things that you would sort of expect Golden Retrievers to love—yet he just has a kindness about him. The way he looks at you is second to none.”

For years, Argos traveled the world with Rufus and Stephen, a constant companion no matter where life took them. Massachusetts, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Provincetown. Denmark, where in 2015 Stephen and Rufus were married. Ironically, Argos hated traveling—even with anti-anxiety medicine, he’d cry the whole time—but wherever Argos ended up, he loved it, and it quickly became their home. In Copenhagen, thanks to the hit reality TV series, “I Am the Ambassador,” Argos became a kind of celebrity, and people would stop them on the streets to take selfies with him.

After three and a half years in Denmark, they returned to America, where they soon added a new Golden to their family as a companion for Argos. Where Argos was anxious, Svend was a “dog’s dog: very lively, very happy, very little anxiety.” At first, they weren’t sure he would be the right fit, considering how his energy changed the dynamic in the house—but he kept everyone, including visiting political dignitaries, on their toes, and this was a good thing. (Laughing, Stephen describes how just the other night, the British Ambassador was visiting, and there was Svend, ever the comedian, showing off and tossing a stuffed animal up and down in his mouth and whipping it around, having the time of his life.) Most importantly, Svend keeps Argos, who will be ten in November, young.

When the coronavirus struck, it offered, along with the most impossible tragedies, the strangest of blessings, especially for a family so often on the go: they found themselves forced to stay in one place. They settled in Nantucket in a house overlooking the harbor. As Rufus made crucial Biden campaign Zoom calls, there behind him, sprawled out on the floor, were the dogs. The four would take long walks—six miles through marsh and little forests and fields and out to the beach—no one else really around, the dogs sniffing for rabbits, Svend out in front chasing birds, Argos lagging a bit behind in his older, arthritic way, but still so happy and at peace. And if they were lucky enough to all have some free time, there’d be moments of quiet in the long afternoons, when nothing was happening and nothing needed to, when they could all relax back in bed and simply be together, the dogs feeling safe and protected, everyone close, calm, at ease, in love. This sense of having nowhere else you had to be, nowhere else you wanted to be—this sense of home.

Now that life is opening up again, though, Rufus is soon to be back on the road, and his new prospective position traveling with the president overseas means he’ll be gone even more, perhaps, than ever before. “By far the hardest part about the move, and Stephen will laugh at me when I say this—is Stephen and the dogs are staying up here.” It’s not the long-distance relationship thing that’s so hard—they’ve done that before—Rufus in Chicago during the Obama reelection campaign; Stephen returning from Denmark to Provincetown to work at his former veterinary practice for summers, or traveling to Kenya to volunteer for a dog health project of the Karen Blixen Camp Trust, where spay/castration clinics were organized for local veterinarians and students to help control the blooming population of stray Maasai dogs. The hardest part is that for eighteen months straight during COVID, Argos and Svend have been following Rufus around, forever right at his side, and how can they know, when he departs, that he’s not somehow leaving them behind? “I am trying to figure out how can I communicate to them that this isn’t some sort of abandonment. The human-to-human stuff is easy, but the dog stuff is much more complicated. I’m feeling enormous guilt about it.”

“Rufus has tried talking to them via FaceTime,” Stephen explains, “and unfortunately, they don’t seem to react.” “It’s so annoying,” Rufus continues, “because if you put on Animal Planet or there’s a dog that comes on TV, Svend barks at it. But if I’m on the iPad, my own voice and my face, he couldn’t care less, which I just don’t understand.”

As in the past, they’ll all manage—which for the most part means doing everything they can to spend every weekend together—at home, where the dogs are.

Argos and Svend out for a walk in Concord, MA.

Photo by Shannon Shaeffer

The Privilege of Grief

Stephen’s first Golden Retriever, Aubrey, lived for almost seventeen years. Soulful and empathic, he was a therapy dog, and Stephen would take him to nursing homes and hospitals to share his calming nature with others in need—though Aubrey often offered similar solace to Stephen, himself. “I went through some dark days back then, and he is the one that pulled me through. He sort of lived for me. And I lived for him.”

So often we talk about how we need our dogs, but too easily forgotten is how much they need us. As Stephen mentions, “We have to make sure that they’re fed, they’re walked, that if we go away, someone takes care of them.” And yet strangely, this is one of the greatest gifts dogs offer us. As Rufus puts it, “They provide a routine and a consistency in your life that can drive you towards a sense of purpose.” He goes on to recall one of the darkest days in their recent history—the morning after Donald Trump was elected president—when he and Stephen found themselves sunk in deep depression and couldn’t get out of bed. “Long story short, it was Argos who got us up. And he was being sort of empathetic, because he could see we were hurting—dogs are so intuitive—and so there was a sense of, I love you guys. It’s gonna be okay. But also, you got to get out of bed. Because this is ridiculous. You can’t just lie here all day long. I have to eat, I have to take a walk. And this idea of being needed—I’m grateful for that.”

Stephen is grateful for it, too: “Our travel and our days all revolve around our dogs. And so they kind of guide our lives, and I think there’s something extraordinary about that. We give that to our dogs very willingly.”

It’s odd to think of it that way—that we so willingly sign up to have these four-legged creatures run our lives—but that’s kind of what we do. (Laughing, Rufus mentions their Facebook and Instagram accounts, how at least every other picture is of Argos or Svend.) But of course, the return on it is beyond compare. It is, perhaps, a forgotten part of the grand bargain: dogs give us the gift of letting us take care of them—of letting us love them—for what else is love, in the end, but showing up?

And having to show up for another creature beside yourself, it expands your life—something is bigger than you now, more important—it expands your heart. With a dog in your life, suddenly, you, too, have no choice but to be in love.

Of course, really loving something, as we inevitably do with our dogs, makes us vulnerable to loss, to grief. And no dog lasts forever. “A Golden’s average lifespan is ten to twelve years old,” Stephen notes. “So, every day beyond that with Aubrey was a gift; every day I was grateful. And because he lived to almost 17, I had, what, four or five years to prepare? But you’re just never prepared.”

Yet the grief you feel when your dog passes on: that, too, is a gift. “I would always remind clients of mine who lost their animal that the grief is real, every bit as real as losing family. And the level of pain that they feel reflects the depth of the love that they had for that animal and the animal had for them—because if they didn’t have that connection, that bond, then there wouldn’t be that sense of profound loss. And so I try to remind them to accept that as a tremendous gift, that they feel such grief, because many people don’t experience it.”

This is the risk, and the reward, of having a dog. Something in you will be awakened, opened—something soft and true and, until this moment, at least partly asleep. And sure, you could say life would be easier if you kept your heart guarded and closed off, if you never dared to love, because then you’d never have to feel the pain of loss. But as Rufus and Stephen remind us, grief is a privilege. It means you have truly loved, and truly lived. It means that, like a dog, you have been brave enough to lead with your heart.

Or, as Stephen puts it: “Wouldn’t life be less full, if you hadn’t had that experience?”

subscription

LOVE, DOG