Haiku for the Dog

You could eat me if

You wanted to, but you don’t.

Want to, that is. Right?

When we open ourselves to the possibility of love, we open ourselves to the possibility of breaking; when we open ourselves to the possibility of breaking, we open ourselves to the possibility of being made whole again. Almost one year after Booker died, we adopted Otter—part Catahoula leopard dog, part Irish setter mix, and part otter, it seemed. That mound of fuzzy head. During another Petfinder binge, I found his tiny half-speckled face—a puppy Phantom of the Opera. His name was Knight and he lived in Jackson, Tennessee. When I spoke to his foster mom, Carol, on the phone, she told me he was so small that she had to watch for hawks when she let the puppies out of the barn for fresh air. After we’d officially adopted him, he came north one night on a truck full of puppies and dogs and I drove to a nearby horse farm to pick him up. All the humans gathered at the truck door, and one by one they brought the puppies out. “Knight!” a man finally said, holding him up in the air. The whole crowd cooed at how adorable he was. He reminded me of the first illustration of Wilbur in Charlotte’s Web. Ears back, eyes wide and vulnerable, belly out. His little body, partly coated in dry poop, went completely stiff, the way animals freeze in the face of uncertainty. I walked up and took him in my arms and brought his face to my face. It took a minute, then his whole body wagged. This struck me as a remarkable moment in a dog’s life—and proof to me that dogs are optimists. His glass half full, he took me as a good thing—my glass half dog—and a good thing I would remain, unless, of course, I proved to be a bad thing.

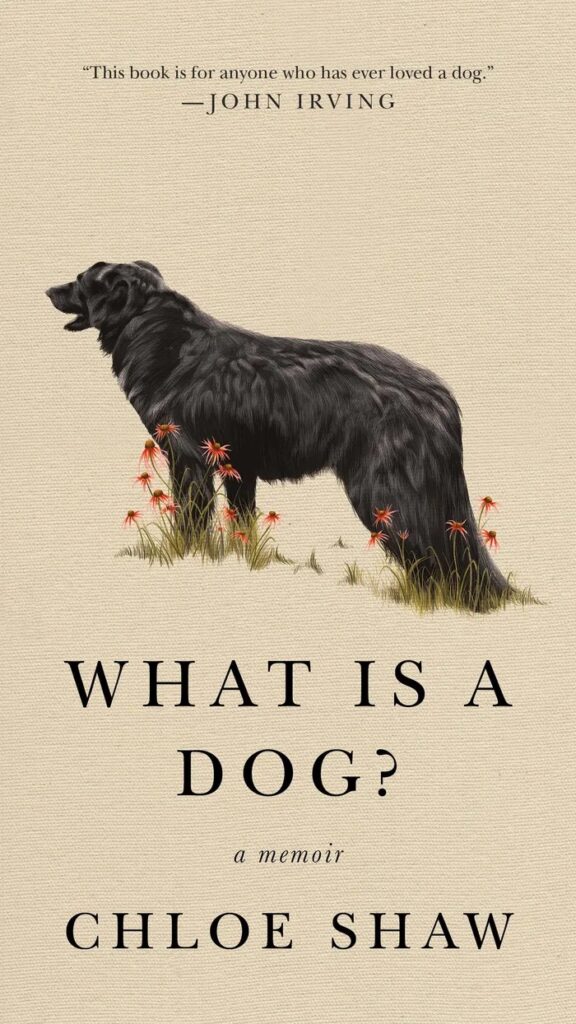

The cover of Chloe Shaw’s literary debut

At his first vet visit, Heather told him, “You’ve got some big paws to fill, mister.” She was right. But, oh, my kids were at such sweet ages for a puppy—four and seven. Though, like adopting Safari, Otter was my idea (or my stubborn, even selfish, insistence, I can say now), my husband was making a sound when petting him I hadn’t heard him make since Booker died. A soft, low hmmhmmhmm accompanied by scratches behind the ears. But what was most moving was seeing Safari act as pack leader. I was watching my dog-lineage vision play out perfectly. Safari, who was raised by Booker, was raising Otter now. As with Booker, it took a little while for Safari to warm up. When I first introduced him to his new little brother (I presented him with what I imagined would be of most interest: Otter’s back end), he took one sniff and turned his head away in what can only be described as doggie disgust. He even did this to me when he could smell the puppy all over my clothes and hands. But I gave Safari his space and time and he slowly opened up to Otter on his own terms. He started tracking Otter around the yard and initiating play with him. Otter looked as happy as the little kid on the playground who finally gets the big kid’s attention. Since Safari still had his limits, which would be delivered in quick, growly bursts, Otter had to learn restraint. It was like watching Robin Williams try to restrain himself before a lit crowd. Just like Booker taught Safari, Safari taught Otter all the dog stuff, too. This is where you pee. This is when you bark. Enough is enough and get out of my face already. I could see it happening before me and felt Booker there, too, maybe one step ahead of Safari, as Safari ran maybe one step ahead of Otter, who ran maybe one step ahead of the trail of dogs yet to come—but all of whom would always be following that first one, Booker the swashbuckler, the cinnamon roll, the sound of Sunday leaping deep in the woods. Eyebrows. Legs. Black-spotted tongue of wonder. Otter has a black spot on his tongue, too.

Though as much as Safari shaped the dog Otter is, they are supremely different beings, operating as differently inside the house as out. Safari, the gentle soul, seeks out in his downtime the quiet corners in which to perch. He likes to curtail any possibility of something sneaking up on him. Otter, on the other hand, is all in all the time. He wants to be where the action is, where the people are, where life most boldly buzzes. “Otter’s the happiest dog in the world,” my son Jackson likes to say. I always wonder if in this there is a tinge of me at his age—that this is his wanting to be the dog. But happy is right. When he greets someone his whole body wriggles with the same absurd theatrics as Steve Martin and Dan Aykroyd’s Two Wild and Crazy Guys. And when I say “someone” I mean everyone, anyone. His excitement is like a Ping-Pong ball let loose in a glass house.

His facial expressions, too, are fantastically revealing. A lovely psychologist I know who works with children has a bowl filled with slips of paper on which she has written an enormous array of emotions. Worried. Happy. Scared. Frustrated. She asks patients to pick out the ones they have felt that day to demonstrate how many feelings we can legitimately feel—even simultaneously. If she asked Otter to do this exercise, I am certain he would pull out every last one. If humans have twenty-seven different emotions, Otter has at least one hundred forty-nine. He seems to run through the entire course of them hourly. He is fantastically sensitive, responding to voice, action, and light with equal enthusiasm. While Safari merely pretends to have a genetic predisposition to chewing bones, Otter receives such toys as if Santa himself is handing them over. He gently takes them in his teeth, and his ears go limp as if he’s overwhelmed at deserving such an honor, and he does little wags like he’s the luckiest dog on Earth but he doesn’t want to celebrate so much that it seems braggy.

Otter always seems to be saying, YES!! ME!! before he even knows what is involved. The only things that give him pause are watching me pick up his poop, which he does with a combination of pity and despair, and encountering something new, something that wasn’t there before. If he happens upon a room with rearranged furniture, he freezes in the face of Something Different and growls. “It’s okay,” I say, walking over to it so he can, too. He always wags at the revelation and comes closer to sniff. He once had a ten-minute early-morning standoff with a chair I’d moved to the center of the patio for a self-timed picture of the kids and me the afternoon before. He had the same thing with a neighbor’s statue of Mary.

***

Otter as a puppy, Safari looking on

Chloe Shaw

Otter planted his feet and growled. There was a wheelbarrow where there hadn’t been one yesterday. “It’s okay,” I told him. “It’s a wheelbarrow.” He wagged as we got closer and felt the okay of it, the way I also had to ease into new things post initial growl, trying hard now to be fine being fine and not fine. I walked him over to the wheelbarrow so he could sniff it, declare it harmless, the way my mom had once taken me to a birthday party early so that I could watch the man turn into a clown to make the clown less scary. Otter sniffed the wheelbarrow all over, his nose twitching back and forth and his wag widening. What an act of faith it is to listen to a dog, to be vulnerable, to feel your body learn from his, and, when a dog says he’s had enough of the wheelbarrow, to believe him.

As the wheelbarrow and we parted ways, I thought of that thing people say about dogs (and children), that you end up with the dog (or child) you need most. Just like Jackson had taught me the most about my own emotional world, Otter had most boldly revealed in me my latest—and last—gasp at hiding in him. He wouldn’t let me. He was the first dog I’d been unable to hide in. He was too dog. Right around the duck pond it hit me: he was the most dog dog I’d ever known. He felt more wolf than human, which explained why the back of his head smelled like smoke and woods. My other dogs had always felt far more human than wolf. I’d always been able to approach my other dogs as friends, peers even, but in order to best know my dog Otter, to be my best for him, I had to come out of my comfort zone and approach him as precisely what science says he is: a dog, a tamed wild animal in our midst. I felt a bit startled by this as we walked, Woman and Dog, down the road. He looked completely different to me than he had just one minute before. He wasn’t Robin Williams or Steve Martin, he was 99.9 percent Canis lupus and it was nothing short of a miracle to be walking next to him, watching his hair ruffle from the muscles underneath, his nostril slits morphing like deep squids at the staggering particles of air I was too human to touch, to hear his jagged claws cleave the road next to my luxurious layers of socks and boots. At its starkest, the distance this revelation created between us reminded me of the foolish man and wise dog from Jack London’s cautionary tale “To Build a Fire.” As the pair heads into the Yukon on a dangerously frigid night, London writes, “There was no real bond between the dog and the man. The one was the slave of the other. The dog made no effort to indicate its fears to the man. It was not concerned with the well-being of the man. It was for its own sake that it looked toward the fire. But the man whistled, and spoke to it with the sound of the whip in his voice. So the dog started walking close to the man’s heels and followed him along the trail.” (Though my voice has never had the sound of whip in it, only belly rubs and treats.) For once, I stood with a dog and felt as wholly in my body as the dog felt in his. It felt exhilarating, though with a strange side effect. As we walked back on the other side of the street, predictably stopping at the scarecrow, rock wall, sewer, I found myself fearing something I’d never feared before. Dogs. If Otter’s wolfness made me feel better as human, then what was a dog to me now? The mere concept of a dog (essentially a wolf we’d negligently invited to supper) suddenly seemed bananas. Why on earth would we bring all these beasts into our home only to be eaten by them?

Chloe and Safari, with Otter at play in the background

Chloe Shaw

As we neared the corner where we cross back over to our house, I started experiencing this fear from the outside, as if from a me outside of me. I imagined bumping into someone on my walk and telling them exactly what was going through my head. I was even able to laugh a little at the absurdity of it—not that a fear of dogs is absurd. I think a degree of it is necessary to living amid them. When strangers ask if my dogs are friendly, I always say, “Yes, but they’re also 99.9 percent wolves.” Who are we to think we can predict the behavior of an animal even half the time? We can train them earnestly and behave for them, but they are animals nonetheless. What felt absurd was that anyone who knew me and my dependence on dogs would have found this whole development preposterous.

When I told my husband, Matt, about the walk that day, about the dog fear and the presence of this outside Observer Me that almost made the whole thing funny, he told me what I was doing—what that Observer Me was doing for me—was inviting the fears in. Letting the dogs in, is how he put it. He told me that I’d moved from hiding within my fears to interacting with them. This felt good. He is a doctor, after all.

Understanding better what Otter needed and, through his more complicated presence, what we as a family needed, I could get to the work of training all of us. We could get to the work. This made the whole situation less nerve-racking, more satisfying. I wasn’t alone with it anymore, trying so hard to love Otter in a vacuum. I wasn’t alone. Though I had been hoping it would be unmitigated love, it was Otter’s complicated presence that brought our family together, as we surrounded the big pup who was essentially telling us that in order to live as a dog with ease, he needed more information and reassurance. The good news was, he was highly trainable, super treat-oriented, and driven to please. But if he wasn’t getting clear signals, he got lost in the murk, and, as happens with any of us, the murk rendered him anxious and confused. It felt empowering to see all of this now, and to see such a clear path toward helping him. After all, Otter was the dog who in all of his ripe, rippling dog-ness had made me respect what a dog is more than any other dog before. Oh, I’d loved my dogs, I’d breathed my dogs, I’d done anything to make them happier, more comfortable, in every moment I could, but he’s the one who pulled me closest to their specific nonhuman needs. He reminded me that he wasn’t me in dog form but a beast, a once-wild animal living in my home. He demanded an entirely different relationship from me, and I was listening. Because of him, I try my best to approach dogs now as dogs, to give them their best dog life, not the best life that I, their human, want for them. It has undoubtedly necessitated a big mental shift, but it’s one that feels welcome and relieving. It is a challenge to me and a necessity to them that I get it right. Dogs are now more than ever a subject of my curiosity, not mere fuzzy receptacles of my grief and heart, though Lord knows all they still carry. Like everyone I love, they tell me what I need to know. If I listen.

EXCERPTED FROM WHAT IS A DOG? COPYRIGHT © 2021 BY CHLOE SHAW. EXCERPTED BY PERMISSION OF FLATIRON BOOKS, A DIVISION OF MACMILLAN PUBLISHERS. NO PART OF THIS EXCERPT MAY BE REPRODUCED OR REPRINTED WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER.

You can purchase a copy of What Is a Dog here.

subscription

LOVE, DOG